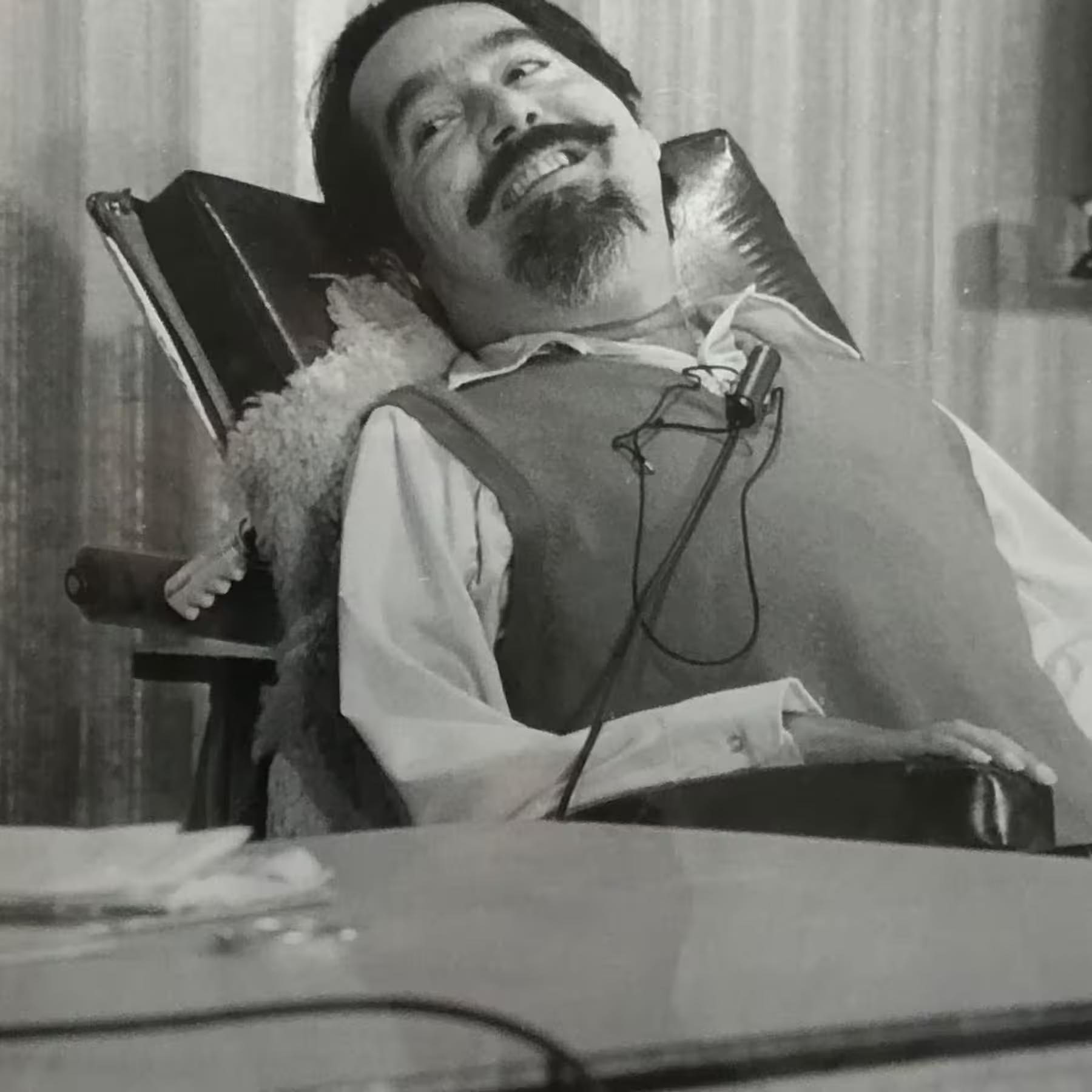

Ed Roberts, Activist

Our Man on the Moon

The first 'severely disabled person' to attend a top ten University was seen as both a hero and a freak

True stories of higher education of Ed Roberts, as told by himself in 1993

"We tried cripples, and it failed."

It was a bitch to get in—I mean, they said, 'Well, we tried cripples, and it failed.' This was 1962. In the meantime, I had gotten my associate's degree from San Mateo Community College with high grades, so they couldn't legally refuse me, but "We tried cripples, and it failed!" I love that!

They told me there wouldn't be anywhere for me to live, that my iron lung wouldn't even fit into a dorm room. So, I went to see the Dean, Arleigh Williams. He was a little freaked out by me, as most people were then, but he sent me up to the Student Health Service at Cowell Hospital to talk with the director, Dr. Henry Bruyn.

If you find a way to make people mobile, it changes their personality

If you find a way to make people mobile, it changes their personality. I've watched babies, children who are a year or two old, paralyzed and unable to move, get an electric scooter or something, and within ten minutes, their personality has changed from totally passive to so aggressive you wonder what they're going to do next.

A young man, Don Lorence, who came into our program at Berkeley, all he'd done for fifteen years was sis in his room. And this guy was a genius with electronics and computers. He's built all these things.

When he came to Berkeley, we could hardly hear him. You had to get really close because he wasn't used to talking to people at all.

We gave him a power chair on the first day he got there. And we lost him! We couldn't find him. Finally, the campus police brought him back. They'd fished him out of the creek! Berkeley has a lot of hills. He was going up the highest hills and putting his wheelchair into full speed. And that day, he came in, and I could hear him. He was just totally exhilarated by the ability to move and to do things.

Ed Roberts

She's on my lap; we're heading off into the sunset

I had to fall in love before I learned to use a power chair. It was in 1967 or 1968, I think, I fell in love, and it was terrific, a great feeling. It became ridiculously inconvenient to have an attendant pushing me around in a wheelchair. Really difficult to be intimate and to be alone.

I remember them putting me in the [power] chair, and I remember almost immediately crashing into the wall, but that was a thrill! All of a sudden, I could do it. Sometimes I'd go through doors and not be able to get out…lots of things I had to learn. But I learned how to drive a power chair in two days. Two days later, she's on my lap, and we're heading off into the sunset. I tell you, that was motivation.

When you're highly motivated, you have a lot of energy. You can often do things you never thought you could. After I got my power chair, I realized that people had to confront me. Suddenly, there was no one else there. That was very important to me.

Those early power chairs weren't the safest.

Later, it must have been 1972 or 1973, I was with my dog. His name was Tremor; he was a wonderful dog, a malamute-shepherd, and he loved to go for walks. By that time, I had reasonable control of the chair. But I was braking, coming down a hill, and I blew a transistor. On one side was a creek, and on the other side was a big hole. I remember riding that chair all the way down to the bottom of the hill, because it went full speed forward on one side, crashed into a tree, and finally stopped. So those early power chairs weren't really the safest.

I learned to have extra transistors and how to install them, so I could describe how to install them to someone.

'These brave souls, these helpless cripples…' Boy, did we play it up

The battle [that brought The Rolling Quads together] concerned the second counselor the state Department of Rehabilitation assigned us. At first, we had a wonderful counselor, and then they sent us a bookkeeper type, Lucille Worthington.

On her best day, Lucille Worthington may not have been a charming person. But at her worst, she was an accountant who wanted to cut costs. It was all federal money by that time, but she still wanted to cut costs.

From the very beginning, she started threatening: 'If you don't give me top grades, I'll cut off your money.' I was working on my PhD, and she tried to assign me subjects to write about. We were on our way to freedom and independence, and nobody was going to stop that.

Some of us had been locked up all our lives, in nursing homes or state homes. She decided to expel three of them from school! She had decided that they would never be able to work after graduation. (She was wrong in all three cases, by the way.) The rest of us got together and fought it.

Ed Roberts and Judy Heumann

We went to the University and finally to the state legislature. We talked harder and longer to the newspapers. Several papers did stories saying how awful it was for these kids to be kicked out, and how [VR] was threatening this program. It was the only one in the world! One where people were actually becoming independent and going to work! These brave souls, these helpless cripples… Boy, did we play it up.

A few weeks later, our friends were reinstated at the University. It turned out to be one of the first times in the history of state rehab that clients had ever forced the department to get rid of a counselor. We wanted her fires, but they transferred her and then retired her.

As Saul Alinsky says, it's essential to win that first battle.

People expected us to fail. We didn't.

People expected us to fail. That didn't happen. We became powerful. We stuck together; we drew the line of what was unacceptable. There were times when the word 'no' was inappropriate. There was no question that we had control of the program.

The first curb cut in Berkeley

We got the city to do the first-ever curb cut on Telegraph Avenue. The city wanted to know why we needed curb cuts: 'We don't see you people out there.' – you know, that Catch-22 thing they do.

So they put in the cut, and older adults liked in, and then women pushing baby strollers liked in, and they put in more cuts, and more of us were out there.

We had this political clout with the city. They had to listen to us in a much more realistic way. All things change when you get political power.

Ed Roberts rafting

The first attendant travels at government expense.

We just got stronger and stronger as more people came in. People came from all over the U.S. to see how these severely disabled people were going to school. The University found it a matter of prestige to back us. They began to see that the future was in serving more disabled people.

What was to become the first CIL started on campus. I worked with the federal government as a consultant on that in 1968. It was my first trip to D.C., my first plane trip, the first time the government had to pay for an attendant to accompany anyone.

We had to go through a few bureaucrats to get that accomplished. They were saying: 'Why are two people coming when we only invited one?'

They brought me in to work on a special student services program for racial and ethnic minorities. As that bill was going through the House, one guy added a clause that 10% of it had to go to people with disabilities. I helped write the guidelines for that.

We used that to set up a program that involved self-help, an attendant pool, and working peers.

Our job was not to control their lives but to help people take control over their own lives. It works fantastically, as you know. It works like crazy.

Society's expectations of us have tremendous power.

Whenever we start by believing that people can't do it, we set up all these systems to do it for them. Charities do that. At the University of California, Berkeley in the beginning, people's attitude was that I would get my PhD and then go live in a nursing home. Society's expectations of us—very low expectations—have tremendous power over us. Our helpers, for instance, were so fearful that we would get out into the world and die.

IL is something else. IL is independent.

We were very clear philosophically. We were beginning to talk about disability issues as civil rights issues.

Ed Roberts